Technology has been one of the hallmarks setting humans apart from other life forms on this planet. From the primitive flint hand axe to the satellites we don’t even think about that make modern worldwide communication possible, humans have used technology to make up for our physical limitations and to improve where we live and how we live.

Ever since we saw a bird fly, we’ve wanted to do likewise. We dreamed of flight and put it in our myths. We flew in stories long before any human achieved liftoff. Kites and balloons were our baby steps. Then the airship ruled our imaginations. On the eve of World War II fixed-wing, heavier-than-air passenger aircraft crossed the Atlantic. Even if the Hindenburg had not burned, the airship had been rendered obsolete by the Boeing 314 Clipper flying boat in 1939.

The Second World War saw the perfection of the helicopter, the building of the long-range heavy bomber, and the invention of the jet, as well as the invention of the long-range ballistic missile. Suddenly, in 1945, such things as balloons, blimps, and rigid airships seemed nothing more than relics of the past.

The balloon has been relegated to hot-air sightseeing excursions, for the most part. The blimp has been reduced to a novel sightseeing experience or eye-catching advertising. There continues to be talk of lighter-than-air heavy lifters for long-distance cargo hauling, but they continue to remain the stuff of dreams.

However, one of the dinosaurs is making a true comeback. Namely, the autogyro. An autogyro? What’s that? At the risk of oversimplifying, it’s an airplane that uses an unpowered rotor instead of wings to achieve lift.

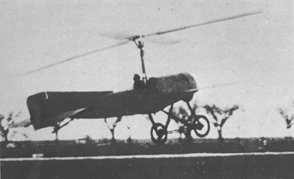

Juan de la Cierva wanted an airplane that could fly safely at low speed. To accomplish his desire, he invented the autogyro. The first successful flight was on 9 January 1923 in Madrid. Below is a picture of the first Cierva autogyro.

Cierva got his wish. Sustained, lazy low speed flight is what the autogyro excels at. It can’t hover like a helicopter because the rotor is not powered. The rotor relies on the forward movement of the plane to make it spin and provide lift. Despite its inability to hover, the autogyro has a distinct advantage over the helicopter: cost. They are cheaper to buy and cheaper to operate. They also have a big advantage over airplanes in that they need very little runway to take off and virtually none to land. An autogyro can be in the air using no more than 30 to 200 feet of runway. An autogyro can’t stall, like a plane, and doesn’t end up in a tailspin. Cierva was certainly on to something.

Below is a later Cierva autogyro:

So why didn’t the autogyro take off? A couple reasons. Cierva was the main proponent of the autogyro. After all it was his baby. His death in a plane crash in 1936 was a major blow to those promoting the autogyro. The second reason was the helicopter. The principle of the helicopter (which the autogyro also uses) goes back to 400 BC and the Chinese toys that probably most of us played with as kids.

The first successful helicopter, the Bréguet-Dorand Gyroplane Laboratoire, built in 1933, took its first successful flight in 1935. In 1936 and 1937, the Focke-Wulf Fw61 was setting world record after world record and the world forgot Cierva and his autogyro.

Below are pictures of early British autogyros, which were soon eclipsed by the helicopter.

A good idea tends to stick around and the autogyro is a very good idea. The late ‘70s and early ‘80s saw the birth of the ultralight aviation movement. People wanted more than just hang-gliding. They wanted to fly and they wanted their desire to be affordable. Enter the autogyro, or the gyrocopter as it is often called today. Aside from personal use, many cash-strapped law enforcement departments are turning to the autogyro because it is a cheaper alternative than the helicopter. The autogyro’s ability to stay in the air at very low speed makes it a viable alternative to the helicopter for crowd control, traffic control, and city surveillance. And because today’s autogyro is small, it can easily go where planes and helicopters can’t. Versatility is always a plus.

Here are some modern autogyros. Aren’t they beautiful?

Once again an old idea, which some thought obsolete and dead, has made a comeback — thanks to modern technology, brought about by the wonderful machine age.

These autogyros are so cool, I think I’m going to get me one. They have to be better than bucking traffic on a clogged freeway. And weren’t we supposed to have flying cars by now anyway?

Share This!