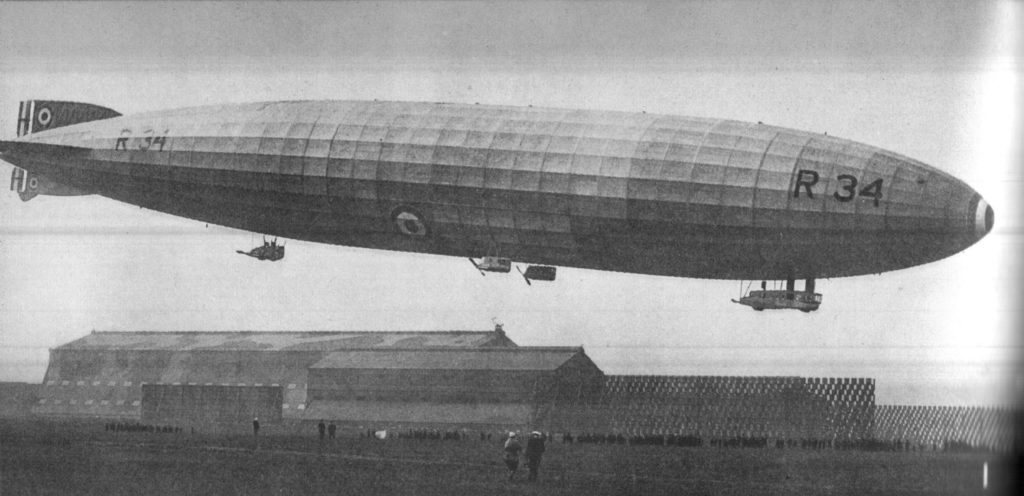

The R 34 over the Royal Naval Air Service station at Pulham, Norfolk in 1919.

Throughout the morning of July 13, messages of congratulations poured into the airship’s wireless room. King George, the chief of the Air Service, the Board of Admiralty, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, among many others.

From General Maitland’s log:

6.20 am—Over Pulham. Quite a number of people on the landing ground despite the early hour. Scott makes two circles of the ground, and puts the ship gently down into the hands of the landing party. Time of landing, 6.57 am. Total time of return journey from Long Island, New York, to Pulham, Norfolk, is therefore 75 hours and 3 minutes; or 3 days, 3 hours, and 3 minutes.

Seventeen years later, the faster Hindenburg’s average time from Frankfurt to Lakehurst, New Jersey was 66 hours and 37 minutes; and from Lakehurst to Frankfurt, 51 hours and 23 minutes. Certainly slower than a jet, but far and away much more luxurious. On par with a cruise ship of today.

The R 34 was a military ship. A copy of a 1916 German war zeppelin that had been captured, largely intact. A mere two years later the Germans were building even larger zeppelins, with greater range. A range they felt would enable them to bomb New York City. One of these “X” Class zeppelins, the LZ-114, was given to the French as war reparations. Renamed Dixmude, in 1923 she made a 4400 mile flight and was in the air for well over 118 hours without any problems. Her maximum range was calculated to be over 7400 miles. The specially rebuilt L 59, the Africa Ship, had a range of 10,000 miles and a payload over 104,000 pounds. She could have flown to America, bombed New York, and flown back to Germany without refueling.

At the time and for decades to come no airplane was capable of doing what the L 59, the R 34, or the Dixmude did. The airship in 1919 and in the following two decades was clearly seen as the wave of the future. Land-based passenger aircraft would not be able to cross the Atlantic non-stop until after World War II. The most famous of the 1930s flying boats, the Boeing 314 Clipper, introduced in 1939, could carry 74 passengers during the day or 36 at night, had a mere 10,000 pound payload capacity, and had a range of 3,685 miles. Certainly a plane to rival the Hindenburg, but only in speed. The airship still laid claim to greater range, payload capacity, comfort, and quiet.

So what happened? In part, the airship herself was to blame. Expensive to build, operate, and maintain, no private company was willing to expend the capital. The rigid airships that were in existence were mostly military vessels and as a weapon of war, the zepp’s days had come and gone.

The R 34 is a prime example of government neglect. The British press hailed the event and the Air Ministry ignored it and its potential for future military application. In fact, the Air Ministry went to great lengths to scrap their rigid airship program—completely ignoring the role the rigid airship could have played as a transport ship in supplying far-flung and isolated military installations with speed and efficiency. Much as the L 59 had tried to do in 1917, in her attempt to resupply the army in German East Africa.

Then, as now, the rigid airship, while not the fastest aircraft, had the ability to carry tons of cargo vast distances to anywhere in the world. The airship needs no airfield or expensive airports. The problem of huge landing crews was solved by the US Navy. A dozen men and a motorized mooring mast handled the 785 foot long (239 m) USS Akron and USS Macon.

More than anything, our desire for speed killed the airship—in spite of its practicality.

Yet, in the early days of aviation, it was Count Zeppelin’s dream that conquered the skies. The crew of the R 34 deserve high praise for their brave accomplishment. Doing what no one had done before.

Today let’s take a moment to celebrate their great achievement.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this touch of Zeppelin Mania. As always, comments are welcome. Until next time, happy reading!

Share This!