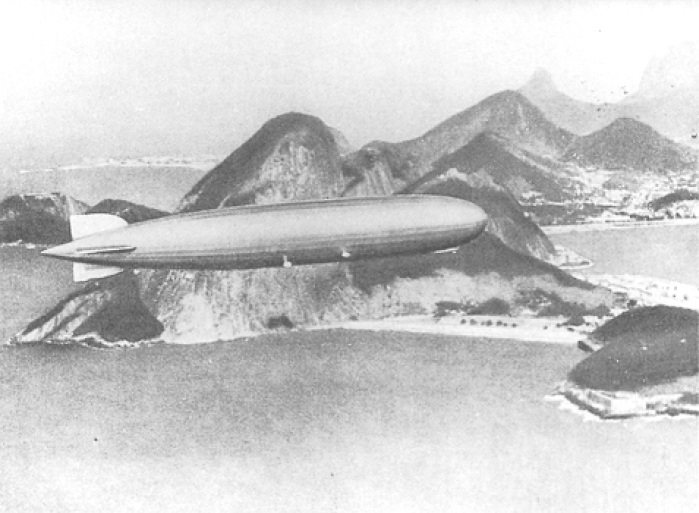

The Graf Zeppelin Over Rio

On the Graf Zeppelin

Hugo Eckener (translated from the German by Douglas Robinson)

I have always felt that such effects as were produced by the Zeppelin airship were traceable to a large degree to aesthetic feelings. The mass of the mighty airship hull, which seemed matched by its lightness and grace, and whose beauty of form was modulated in delicate shades of color, never failed to make a strong impression on people’s minds. It was not, as generally described, ‘a silver bird soaring in majestic flight,’ but rather a fabulous silvery fish, floating quietly in the ocean of air and captivating the eye just like a fantastic, exotic fish seen in an aquarium. And this fairy-like apparition, which seemed to melt into the silvery blue background of the sky, when it appeared far away, lighted by the sun, seemed to be coming from another world and to be returned there like a dream…

The mighty hull indeed! The Hindenburg weighed 236 tons, was 13 stories tall, and was nearly as long as 3 football fields. The 7 million plus cubic feet of hydrogen was sufficient to run an ordinary kitchen stove for several hundred years.

The 17 huge gas cells of the R 101 used the intestines of a million cows to provide the leak-proof lining.

However, not only were the ships of behemoth dimensions, so were their hangers. The Goodyear-Zeppelin hanger in Akron, Ohio was so huge clouds sometimes formed and a soft rain would fall.

And as Dr Eckener wrote, those giants of the sky were like something from another world, a dream world. They were exotic silvery fish of immense size and fairy origin.

John R McCormick’s account of seeing the Graf Zeppelin when a young boy fills me with envy. Here it is in part:

Out of the Blue

…I was a little uneasy. Something wasn’t quite right. Suddenly I realized why. We were alone, absolutely alone, and surrounded by a profound silence. That whole land, usually so full of sound and action, was empty and still. Even the animals were quiet. There was no wind, not the slightest breeze.

Into that remarkable silence there came from far away the smallest possible purring, strange and repetitive, gradually approaching, becoming louder — the unmistakable beating of powerful engines. I looked to the west and at first saw nothing. Then it was there, nosing down out of the clouds a half-mile away, a gigantic, wondrous apparition moving slowly through the sky.

“Grandma!” I screamed.

She was out of the kitchen door in an instant. I pointed to the sky. The great dirigible was very low, perhaps because the captain was trying to find some landmark.

There is a wonderful opening scene in the movie Star Wars. A great starship is passing very low and directly overhead so that one sees only the underside. That underside moves deliberately and interminably on and on until at last it is gone. The Graf Zeppelin, moving ever so slowly above us, was like that. We saw every crease and contour from nose to fins. It was so low that we could see, or imagined we could see, people waving at us from the slanted windows of its passenger gondola.

We stood entranced. Slowly, slowly the ship moved over us, beyond us, and at last was gone.

The above accounts and information are taken from one of the books in my library: The Zeppelin Reader: Stories, Poems, and Songs from the Age of Airships, edited by Robert Hedin. A fascinating book. Highly recommended!

Comments are always welcome! And until next time, happy reading!

Share This!