Cosmic, or Lovecraftian, Horror

Cosmic horror is largely, if not solely, the creation of HP Lovecraft. Of whom Stephen King said he “has yet to be surpassed as the Twentieth Century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale.”

There are certain themes that differentiate Lovecraft’s brand of horror from other horror subgenres. Let’s take a look at some of the key themes.

Humans Are Insignificant

It’s a big universe out there. And we don’t know even a fraction of it. As Lovecraft commented often (and I’m paraphrasing), we are an insignificant species on a fly speck. And if there are in fact multiverses, then that fly speck just became innumerable times smaller.

Philosophically, Lovecraft was basically a mechanistic materialist. We exist, but that doesn’t mean we’re more important than anything else. In fact, the universe is indifferent to us. We aren’t objectively special. For Lovecraft, we definitely weren’t made in God’s image. There’s no God, for starters. Rather, he was inspired by the atheistic Epicureans and the theory of evolution.

Therefore, in the typical cosmic horror story there is little focus on characterization. The main character is usually the story’s narrator. We get to know something of him, although sometimes he’s an unreliable narrator.

The focus of the story is on the gradual revelation of that which is hiding behind the narrator’s (and our) illusion of reality. That which is greater than us and views us as we view ants on the sidewalk.

The Great Old Ones, at least for Lovecraft, didn’t actually exist. They were literary devices to convey our position in the vastness of the universe and that the universe doesn’t give a fig about us.

The Heroes Are Loners

The hero of the cosmic horror tale has affinities with the punk hero. He is socially isolated, and therefore frequently a loner. Occasionally an outcast. He is often reclusive, and possesses a scholarly bent.

This puts the cosmic horror hero in the unique position of being able to peel back the veneer of what we think is reality to see the real reality behind it. Often at the expense of his sanity.

Pessimism, or Indifference

Lovecraft insisted later in life that his philosophy was not pessimistic, but rather led one to indifference. A fine line there. Basically, though, there is nothing in the universe that cares about us or values us. We humans are alone on a tiny speck of dust. We are dwarfed by the vastness of space. The very vastnesses of which Whitman sang so positively and eloquently about. For Lovecraft, there is nothing positive about them.

In this, Lovecraft was very much in line with the ancient Greek Epicurean philosophy. The universe was simply chaos. It provides us nothing. We must focus on ourselves and find pleasure and happiness in intellectual pursuits away from the madding crowd.

The Great Old Ones of Lovecraft’s invention aren’t so much malignant or malevolent as that they just don’t give a fig about us. We are inconsequential to them.

However, to us their indifference might seem to be malevolent or evil. But in reality, like us, they just are. They’re doing their thing. If we suffer as a result, well, do we care about the ants we step on?

Therefore the hero in the cosmic horror tale is often incapable of doing much to thwart the cosmic forces ranged against him. The best he can do is warn us of the truth that is out there.

The Veneer of Reality

We live in a dream state, as it were. Lovecraft was fascinated by dream worlds. In The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath he postulates a parallel world only attainable by means of dreams.

Because we are in a dream, as it were, what we see and think to be reality isn’t in fact reality at all. It’s Dorothy in Oz. Only we see a nice old man until Toto pulls back the curtain and reveals the monster at the controls.

The real reality is too horrible for us to comprehend. In our dream state we believe we have value — when in reality we have no value at all. We have no significance in the universe. And by extension nothing else has any significance either.

That is the true terror of cosmic horror: the revelation and realization that we are living a lie. It is the literary portrayal of the Nietzschian coming to awareness of who and what we really are.

That realization is also the basis for the “leap of faith” to find meaning for our existence. Epicurus sought meaning in intellectual pleasure. Nietzsche sought meaning in the pursuit of art; that is, creativity. The Existentialists made that leap to whatever might have meaning for them as individuals. And argued that we do the same.

Not unlike the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius’s statement that “life is opinion”. That is, life is what we think it is. Although, for the Roman emperor, the statement was more an affirmation of the contemporary saying, It’s all in your ‘tude. Because Stoicism is inherently a much more positive philosophy.

Fear Of The Other

We have an innate fear of that which is not like us. This goes back to the very beginnings of the human species when we existed in family units and tribes. Anything that was not us, was to be viewed with suspicion — if not outright fear.

Lovecraft is frequently criticized today for being xenophobic and racist. By today’s standards he was — but in his own era I’m not so sure he was any different than most of his peers. There is a danger in judging the past by other than it’s own standards.

Even today, Western views of what constitutes xenophobia and racism are not universally shared. Which means the question must be asked, what makes Western views any more valid than any other views? That, though, is another discussion.

One thing is for sure — the xenophobia and racism we see in Lovecraft’s stories feeds on our own innate and latent fear of those people and things that are different from us and of our fear of the unknown in general. They feed on our own tribal mentality. The primeval us-them dynamic. The dynamic that made us who we are today: too often judgmental, critical, and suspicious. We and our opinions are good. Everyone else and there opinions are bad.

Throughout most of our history as a species, the tribal mentality allowed us to survive. The problem being that as we developed civilization, many of those survival traits became a hindrance to our working together in a genteel environment. Hence the creation of religious moral codes and cultural mores and folkways to control those “undesirable” traits.

As Will Durant noted, “Every vice was once a virtue, and may become respectable again, as hatred becomes respectable in war. Brutality and greed where once necessary in the struggle for existence, and are now ridiculous atavisms; men’s sins are not the result of his fall; they are the relics of his rise.” Do note that every vice may become respectable again. Something to think about.

In Lovecraft’s worldview, the Other consists of all the impersonal cosmic forces that exist. In his fiction, he personified these impersonal forces as The Great Old Ones. Inter- or Other-dimensional beings who have moved into our territory.

Just as we give little thought to mosquitoes, or gnats, or ants, so The Great Old Ones give little, if any, thought to us. To repeat, they aren’t so much malevolent, as they are indifferent to our existence and survival. Just as we are indifferent to the survival of mosquitoes, gnats, or ants.

Lovecraft is simply positing that cosmically speaking — we aren’t necessarily at the top of the food chain. Something to think about as we venture into outer space. Which was cleverly addressed in The Twilight Zone episode “To Serve Man”.

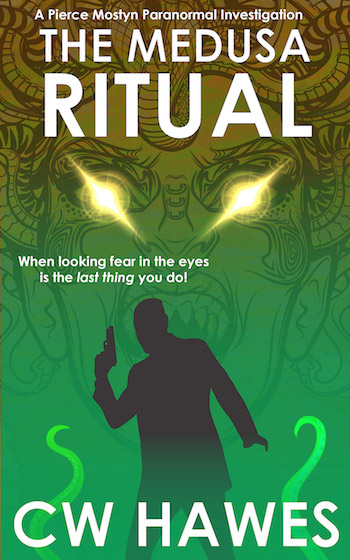

In light of the above, the Pierce Mostyn adventures may not be pure examples of cosmic horror. But we’ll look at that next week.

Comments are always welcome! And until next week, happy reading!

Share This!