Airships. Those behemoths of the sky. Gentle giants that fill us with awe. That still inspire us to dream of their return some 78 years after the end of commercial airship flight. Oh, how we love them!

Yet, given today’s scale of economics, they are on par with the dinosaurs. The giants are gone and all that remains are those semi-lighter-than-air Zeppelin NTs. Something akin to watching birds and seeing in them the gigantic might of the Tyrannosaurus Rex and the monstrous bulk of the Brachiosaurus.

Many books have been written about airships and many more will undoubtedly be written. They capture our imagination. They were the first flying machines to prove the feasibility of flying through the air with the greatest of ease. I’ve written previously on airships. Check out my guest blog post at The Old Shelter for additional information and pictures. This week and next, I’ll tell a little more of the history of those marvelous lighter than air machines.

On December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers inaugurated heavier-than-air powered flight. Their initial flight lasted 12 seconds and the plane flew 120 feet. Their best effort of the day was a 59 second flight, for a distance of 852 feet. Certainly not an auspicious start when compared with the first powered airship flight in 1852 which traveled 27 km (17 miles). Nor when compared with the first zeppelin flight in 1900, which lasted 17 minutes and covered a distance of 6 km (3.7 miles). Clearly, the airship and not the airplane was the wave of the future.

However, World War I changed the picture and changed it dramatically, as wars often do. Airplane performance increased substantially. So much so, the plane proved itself superior to the airship in short distance operation. Mostly due to cheaper operating costs and speed. But for long distance flights, the airship was still king.

From the moment the Montgolfier balloon ascended into the sky in 1783, people started figuring out ways to make the balloon steerable and capable of free flight, independent of the wind.

The first powered flight of an airship occurred in 1852 when Henri Giffard flew 27 km (17 miles) in a steam-powered airship. He flew from Paris to Élancourt. However, the wind was too strong for him to make the return flight. He was, however, able to make turns and circles to show his airship was fully controllable.

Here is a picture of the model in the London Museum:

Thirty-two years later, Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs, in the French army airship La France, made the first fully controllable free flight. The airship was powered by an electric motor. The La France flew 8 km (5 miles) in 23 minutes and was able to fly against the wind to return to its starting point.

Here is a photo of La France:

In the early years of the 20th century, while Count Zeppelin was experimenting with rigid airships (vessels with gas cells contained inside a framework that gave the envelope or hull a fixed shape), Alberto Santos-Dumont was building and flying non-rigid airships (vessels with no framework, relying on gas pressure to maintain the shape of the envelope) in France. He was so successful, he started an airship craze. Soon everyone was getting into the act. Everyone wanted an airship. One of the most ambitious of these early airship men, was journalist Walter Wellman. In his airship, America, he made two attempts to fly to the North Pole and in 1910 attempted to fly across the Atlantic. You can read about his exploits on airships.net.

Here is a picture of the airship America:

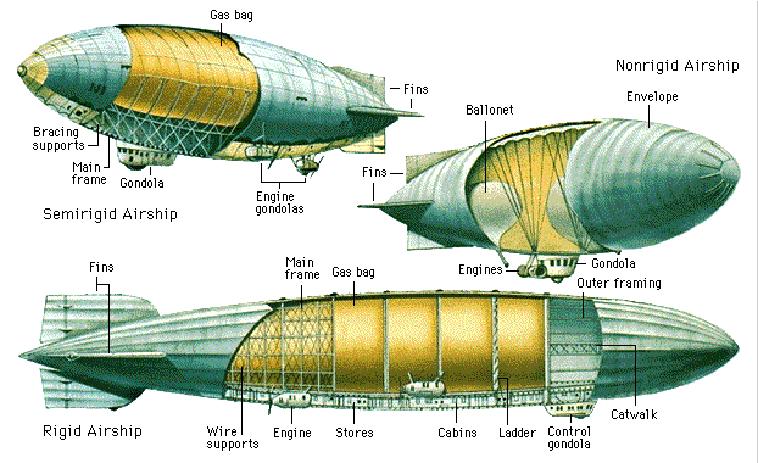

Non-rigid airships are limited in size due to the inherent instability of the envelope or hull. If too long, they may develop a kink should gas pressure become insufficient to maintain the shape.

The solution lay in giving the envelope some manner of framework to keep its shape. A semi-rigid airship has a keel to prevent buckling, gas pressure maintains the envelope’s width. A rigid airship supports the envelope with a framework. The lift gas is contained in cells within the framework. The largest airships we’re rigid in design, due to their inherent structural strength.

Enter Count Zeppelin. For the airship to be a successful passenger liner, cargo hauler, or military vessel, it needs to be able to carry a lot of weight and fly a great distance. The Count understood this and focused on the development of the rigid airship. From 1900 to 1911, numerous improvements were made and lessons learned on how to build and fly rigid airships.

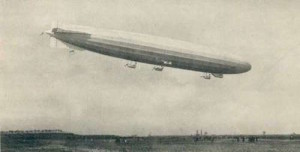

The world’s first airline, the DELAG, went into operation in 1910 and in 1911 the LZ 10, Schwaben, joined the next year by the LZ 11, Viktoria Luise, was making regular flights between German cities, as well as pleasure cruises. By July 1914, the DELAG airships had flown 172,535 km on 1588 commercial flights, carrying 34,028 passengers. With no fatalities.

Here is a picture of the LZ 10:

During World War I the Germans built 90 airships, 73 of which were by the Zeppelin company. All of them were destroyed or turned over to the Allies. What the war revealed was that the rigid airship did not make for an effective strategic bomber. Its strength lay in reconnaissance, cargo hauling, and long distance flight.

A Schütte-Lanz airship, Zeppelin’s main competitor:

Perhaps the most spectacular achievement was by the LZ 104 (Navy ship L 59), known as the Africa Ship. On November 21, 1917, the LZ 104 took off from Bulgaria carrying 15 tons of supplies for the beleaguered German East Africa Army. On November 23, Lieutenant Commander Bockholt received an abort order and the ship returned to Bulgaria, arriving the morning of November 25.

The LZ 104:

The LZ 104 had flown over 6800 km (4200 miles) in 95 hours and had enough fuel for another 64 hours flight time. It wouldn’t be until 1938, when a modified Focke-Wulf FW200 “Condor” made the 3728 mile flight from Berlin to New York City, that trans-Atlantic commercial plane flights began to be conceived of as possible by land-based airplanes. I think it significant that LZ 104 could have flown from Berlin to New York with ease. In fact she could have flown for another 500 miles to Detroit, Michigan or Charlotte, North Carolina.

After the end of World War I, the airship was the only aircraft capable of trans-oceanic intercontinental flight. Next week we’ll conclude our look at the airship, one of the most marvelous machines of The Wonderful Machine Age.

Share This!