Readers become writers when at some point they say to themselves, “I can do that.”

Or they just know the writing life is for them. An intuitive sort of thing.

With the advent of viable e-books, a new breed has risen up. I call them the gold rush writers. They see writing as a get rich quick scheme. And there are quite a few who are making significant piles of money. But as with most prospectors in the gold rush, most writers aren’t making those piles of money. In fact, it’s the middle man who is: the man who sold shovels to prospectors, and the ones selling covers, and formatting and editorial services to writers.

For myself, I cannot remember a time when I didn’t read. My mother read to me when I was young, and, even though she wasn’t a very good reader herself, she instilled in me a love for reading that has never left me.

Along with never remembering a time I wasn’t reading, I don’t remember a time when I wanted to be anything but a writer.

Unfortunately, my parents were of a practical bent and writing was just too dreamy and artsy-fartsy for their tastes. I got no encouragement from them to write.

However, a person who truly wants to write can’t be held back and I did write some during my school years, got one or two things published in the school lit mags, had a play produced in high school, a poem published in a fanzine, and that was about it.

After school, life and family responsibilities took over and the writing got pushed to the back burner.

The bug, though, had bitten and in 1989 I wrote my first novel, a mystery, Festival of Death. The book took me a year to write, but I wrote it. When finished, I sent it out, got a rejection slip, took another look at it, and decided it needed work, as most first novels do, and put it in the drawer.

I made a few more attempts at fiction. Had one or two pieces accepted in fanzines. And then switched to poetry.

Never in a million years would I have thought of myself as a poet, but it was via poetry that I found my initial writing success.

During the 1990s, and into the new century, I wrote several thousand poems, had hundreds published (mostly in e-zines), and eventually became a “name” in the small world of English language Japanese-forms (we’re talking about haiku, tanka, and renga).

The Internet is fragile and its content ephemeral. What is here today, is gone tomorrow. And most of my published poetry is no longer extant. The myriad of pixels have vanished. The e-zines are gone.

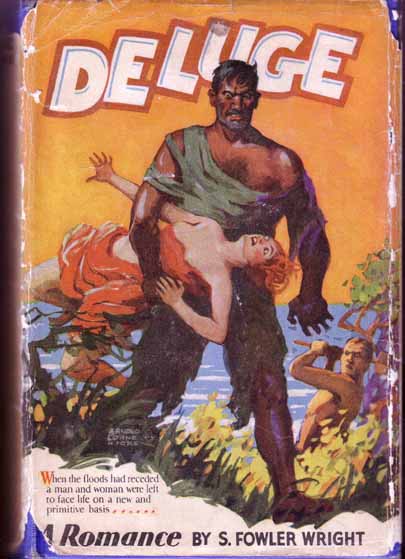

As I approached retirement age the fiction bug bit me again, but this time very hard. Poetry didn’t provide a big enough canvas anymore. I wanted the space a short story or novel provided. I wanted to create interesting characters and saddle them with impossible problems.

And so it was, I gave up poetry and returned to fiction. I had many false starts. Mostly because I thought I had to outline my novel. And I can’t outline worth a darn. When I finally learned there was such an animal as the “plotless” novel, and such a creature as the pantser — I knew I could finally write fiction. After all, I never planned my poems. I was a pantser poet. Why not a pantser novelist?

I never looked back. My first novel as a pantser was a monster of 2000+ pages. A sprawling cozy catastrophe completely un-publishable as originally written — it nevertheless broke the ice.

I’m now revising and publishing The Rocheport Saga as a series. There are currently seven volumes, with more to come.

Next was Festival of Death. I love Tina and Harry and couldn’t let them languish. I hauled the original manuscript out of the drawer, kept the first chapter and the ending, and rewrote everything else. A much, much better novel the second time around, I went ahead and self-published it. And have chronicled many more adventures of Tina and Harry, Tina being Minneapolis’s most unusual private eye.

The life of Lady Grace Hay Drummond-Hay is every feminist’s dream. I don’t understand why no one has written her biography. A fascinating woman who lived in fascinating times: the period between the two world wars. A prominent and well-known journalist in her day, it’s sad to see she is virtually unknown today.

She became the inspiration for my own Lady Dru alternative history novels. Of which I currently have two.

I’ve always loved horror and have several short stories and the Pierce Mostyn Paranormal Investigation series published.

And as long as I have breath there will be more ideas coming from my pen, and that makes me want to jump out of bed every morning and get to work.

The e-book revolution has allowed me to realize my dream. I’ve had enough rejection slips in my day to know I don’t like them — and to know they come from the subjective whim of another person, a person who just so happens to have the title “editor”. But a person who puts his or her shoes on the same way I do.

Editors aren’t infallible, nor are they omniscient. They make mistakes and their knowledge of the marketplace is limited. Most are in fact simply buyers for their publishing houses. And as such tend to be very conservative and not willing to take any chances.

Today’s e-book revolution puts the work of writers before readers — and lets us readers make the decision concerning a book’s future.

However, while writing is easy for me, marketing is a nightmare. And no writer hoping to get his or her work read can avoid marketing. Somehow we writers have to get our books before readers. And we readers will never know a book is out there unless someone tells us it is. There are just too many books for us readers to possibly know them all.

I once read that 3000 new books appear each day on Amazon. Amazon, however, only promotes those books on which it can make money. In the end, those are darn few. Most books, therefore, languish in Amazon’s dusty book basement. And many good books, sad to say, are sitting on those dusty shelves.

Why are good books not seen? Mostly because the author isn’t marketing them, or isn’t marketing them effectively.

Some authors believe in the magic wand. They say, “I’m a good writer and my friends like my book. It’ll sell.” Then they’re disappointed when it doesn’t. And it doesn’t sell because too few people even know it’s out there. One book in a sea of millions is the same as one needle in a haystack. There are no magic wands.

Marketing is difficult. It has few established rules, involves a lot of guesswork, and many years of experience. It also takes money. Maybe not a lot. But if a writer doesn’t have the money, then any amount is a lot.

I’m in that category. I don’t have a lot of disposable income. Therefore, I have to think harder and smarter about marketing. I just can’t throw money at the problem in the hopes of finding a solution. And I know there are no magic wands. I am going to have to do something to get people to find my books. And I want them to find my books. I want more readers. I think my books are good reads. Others think so, too. Those that have found them, that is.

IMO, Patty Jansen has laid out the best course for indie authors to follow if they want readers and would like to make a living from telling stories. It’s my plan to get more readers and hopefully make a few bucks while I’m at it. Art for art’s sake is fine. But it’s better if lots of people can appreciate it — and that takes marketing. And while I’m at it, you can find all my books here.

Even though I’ve moved from reader to writer I’m still a reader. Reading is my favorite form of entertainment. The number of books is endless, they’re fairly easy to find, and one can read anywhere and at anytime.

Currently, I’m reading the delightful Flaxman Low occult detective tales and Seabury Quinn’s Jules de Grandin stories.

Let me know what you’re reading. And the more obscure the book, the better! If the book is by an indie author, and I like it, I’ll give the author a little free publicity.

Comments are always welcome, and, until next time, happy reading!

Share This!