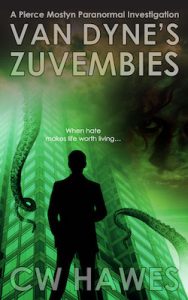

“When hate makes life worth living…”

Cryptozoology is the study of cryptids: those creatures of myth, folklore, legend, and imagination that science sniffs at, and yet may in fact exist. Much like the coelacanth, thought extinct for 65 million years, only to be found alive and well in 1938. Seems science doesn’t know everything.

Writers of the paranormal love cryptids. They are their stock in trade, their bread and butter. Yet, of the hundreds of cryptids available, relatively few find their way into the tales of the paranormal writers.

Way back in 1934, Robert E Howard wrote a story titled, “Pigeons from Hell”, which was published in the May 1938 issue of Weird Tales, two years after Howard’s death.

The story is a superb example of Southern Gothic horror, and features a creature of Howard’s invention, although drawn from Voodoo myth — the zuvembie.

Given the current zombie craze, I would’ve thought someone would’ve made use of the zuvembie before now. To my knowledge, no one has.

So you may be asking, “What the heck is a zuvembie?” That’s a good question, and I’m glad you asked. Let me satisfy your curiosity with a scene from Van Dyne’s Zuvembies:

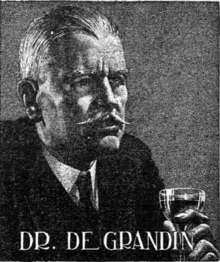

“Can someone please tell me what the hell a zuvembie is?” NicAskill asked.

Dr Heber cleared his throat. “A zuvembie is a creature that is often classed as one of the undead.”

“You mean like zombies and vampires?” NicAskill asked.

“Yes. Although technically speaking, a zuvembie is not dead. Simply changed.” Heber paused a moment to clean his glasses. He put them back on and continued.

“In traditional voodoo, a bokor, that is, a magician, creates a zombie from someone who is already dead. A zombie is a re-animated corpse that does the bidding of the bokor. A zombie is essentially a slave.”

“So there’s no zombie virus?” Jones asked.

“No. That is the stuff of cheap pulp fiction and B-rated movies.”

“So no zombie apocalypse,” Jones said.

Heber shook his head. “I’m afraid not.”

“So if a zombie is a slave, what’s a zuvembie?” NicAskill asked.

“As I said,” Heber explained, “a zombie is a slave of the bokor, created by powerful spells that are cast by the bokor. A zuvembie, on the other hand, has never died. The creator of a zuvembie may or may not be a bokor. However, the creator of the zuvembie has gone through the necessary rituals and been taught the secret of making the Black Brew, which, when drunk, will turn a woman into a zuvembie.”

“Only women can become zuvembies?” Jones asked.

“That is correct,” Heber replied. “Only women.”

“Why?” The question came from NicAskill.

“Because hate and revenge are the motivators and the required emotions to become a zuvembie.” Heber shrugged. “It seems women, as a sex, have so often been viewed as inferior that they and they alone possess the necessary hatred and desire for revenge to become a zuvembie.”

NicAskill sat back in her seat. “Wow.”

Heber, a smile on his face, continued. “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. The zuvembie is the personification of female hate and revenge.”

“So what’s this thing like?” Jones asked.

Heber explained, “According to the lore, ancient lore that predates voodoo and goes back to West African snake religions, once a woman drinks the Black Brew she ceases to be a human. She becomes one with the denizens of the Black World. Friends and family cease to exist. A zuvembie has command over some aspects of nature. It can control owls, snakes, bats, and werewolves to do its bidding. The creature can summon darkness in order to blot out a small amount of light.

“Unless killed by lead or steel, it lives forever. Time means nothing to the zuvembie; it exists, as it were, outside of time. It no longer eats human food, and dwells in a house or a cave much as a bat does.

“The zuvembie cannot speak, at least not as humans do, and it does not think as humans think. However, by the sound of its voice it can hypnotize the living and summon a person to his or her death. And once the thing has killed a person, it can control the lifeless corpse until the corpse grows cold and the blood ceases to flow. The corpse becomes the slave, as it were, of the zuvembie and will do whatever the zuvembie commands it to do.”

“Good night,” Jones said. “It’s a good thing women don’t know about this zuvembie thing.”

“Shut up, Jones,” NicAskill said.

“One more thing,” Dr Heber said. “The zuvembie has but one pleasure in life.”

“What’s that?” Mostyn asked.

“To kill human beings.”

So now you know what a zuvembie is. Pretty scary stuff, coming as it did from the stories REH’s grandmother told him. Nothing like folklore to scare the bejeezus out of you.

Van Dyne’s Zuvembies is at the beta readers, and I’m looking to publish it late June or early July.

In the meantime check out the other Pierce Mostyn adventures. They’re filled with monsters, daring-do, and will convince you to keep the lights on at night.

Comments are always welcome! And until next time, happy reading!