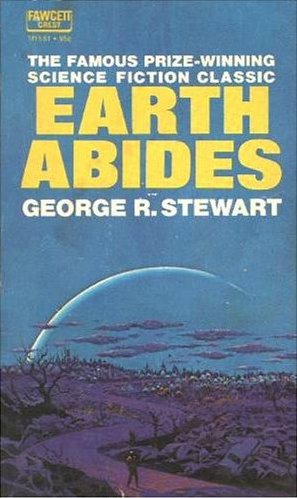

The cozy catastrophe can have no better representative than George R Stewart’s Earth Abides. To the modern reader who is expecting a thrilling nail biter of a novel, oozing zombies at every turn, this is not the book for you.

However, if you are looking for a thought-provoking story of a person, a story of a person’s life, a story about a real person who is not always likable and yet has a vision that rallies people around him, a story of hope and inspiration — than this book is your cup of tea.

Earth Abides is about Isherwood Williams and his life after he survives a rattlesnake bite and a deadly pandemic that wipes out most of the world’s population. While the world of the ‘40s, ‘50s, and into the ‘60s quaked in its boots worrying over a nuclear holocaust, Stewart showed us there are other things about which we need to be concerned. Primary of which is our lack of concern about our impact on the natural world and its counter-impact on us.

When Ish, as he is called, comes down out of the mountains where he has been hiking and discovers the world as he knew it had died in a matter of weeks, we see a person befuddled by the enormity of the tragedy and yet one who as a result develops the resolve to not let knowledge die. He gets a car and drives from his home in California to New York City and then back to California, taking in a grand tour of the devastated country.

What Ish learns is that people don’t know how to survive for the most part and secondly, they never knew what to live for. What really matters in life. Earth Abides is in part philosophy masquerading as a novel. The questions Ish asks himself and what he eventually demands of the group that collects around him are important questions we should all ask ourselves before disaster strikes us.

Ish discovers that the world of businessmen and middle-class values does not prepare one for the real stuff of life. Stewart contrasts a southern African-American family with a Euro-American couple in New York City.

The poor blacks know more of life than the prosperous whites. The African-Americans set about to create a family of survivors: a man, a woman, and a young boy. Ish finds the woman pregnant. They have collected some farm animals and planted a garden. They make Ish realize that is what he needs to do rather than simply scavenge the detritus of the dead world.

The white couple in New York, by contrast, have no children, drink booze all day, play cards, read mysteries, and eat their meals out of tin cans, sometimes to Chateau Margaux. They have not given one thought as to what will happen when winter comes. Ish likes them for they are not despondent over what happened, but he realizes they will not survive because they don’t know how to and aren’t capable of thinking beyond their urban middle-class box.

George R Stewart wrote Earth Abides in the 1940s, it was published in 1949. His language is a bit dated by our politically correct standards and his science is also. But Stewart’s vision of hope is timeless. He was a professor of English at UC Berkeley. He was educated at Princeton, Berkeley, and Columbia. Dr Stewart was something of a polymath and unfortunately is virtually forgotten today. He wrote widely on a great array of subjects.

Stewart’s vision of a possible future for the human race is an interesting one. In a time when blacks were largely ignored by the greater society, Stewart shows them to hold the future in their hands. They know how to survive. Ish, whose name is symbolic, Ish meaning man in Hebrew, and is white marries a woman, Emma, who is at least partly African-American. That in an era in which miscegenation was very much taboo. Emma’s name is also symbolic for it means whole or universal. Ish calls her “the Mother of Nations”.

The style of writing is a partial throw back to the Victorian third person omniscient, which I find to put a certain distance between the reader and the story. For the story is told to me by an all-knowing narrator. Earth Abides is somewhat in this style and therefore creates a certain distance between reader and story. If one can overlook the manner of the telling, then one will find the classic that this novel truly is.

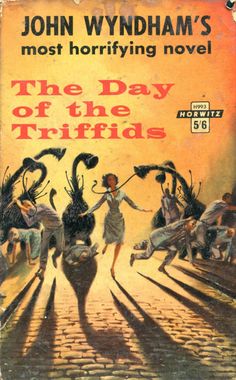

The detractors of the cozy, and I’m primarily pointing a finger at Brian Aldiss and Jo Walton and those websites that repeat their criticisms, have so narrowly defined what the cozy is, as though it is solely a British thing, they have turned off readers to a truly great treasure trove of fiction that can stimulate the best in us in the here and now. Earth Abides busts wide open what very much appears to be the self-loathing of Aldiss and Walton. Their own dislike of their own middle-class existence.

In Earth Abides, we see a college student collect together a band of largely working class people and craftsmen. He draws inspiration from a class and race that was marginalized in his day and age. The main character breaks the old taboos in his quest for a better society, but realizes he can’t do it alone. Earth Abides is not a tale filled with thrills and spills. It is one filled with ideas and filled with hope for a better world. Something we all want. It is the classic cozy catastrophe.

Comments are always welcome! Until next time, happy reading!

Share This!