While pipe smoking is not what it used to be, as is smoking tobacco in general, fictional pipe smokers (and their creators) abound.

There’s something about a pipe that conveys an image cigarettes, cigars, and not smoking simply doesn’t.

The Pipe Smoker

The pipe smoker is seen as a thinking man. A man of intelligence (Einstein was a pipe smoker). The pipe smoking man is not a rush about. His approach to problem solving is more measured and thought out.

Compared to the cigar and cigarette smoker, and also the non-smoker, the pipe smoker exudes the best qualities of a man.

The greatest generation were in large part pipe smokers. Back when I was a kid, there were an estimated 30 million pipe smokers. Today that number has dwindled to 3 million. And men are in a crisis, being assaulted left and right by extreme feminism. Maybe men should man up and go back to pipe smoking. It is a thought.

Fictional Pipe Smokers

But on to fictional pipe smokers and their creators, which is the subject of today’s post.

Sherlock Holmes

Probably the most iconic of fictional pipe smokers is Sherlock Holmes. He was an inveterate pipe smoker. The Persian slipper filled with his shag cut tobacco. The dottle he collected to be smoked first thing in the morning (I have to say here, yuck!). And of course, the famous three–pipe problem (nicotine stimulates thinking).

Philip Marlowe

Philip Marlowe smoked a pipe, as did his creator Raymond Chandler. And Marlowe is one of the most iconic of hardboiled detectives. He was also a rather introspective man. Something that is part and parcel of being a pipe smoker.

Hobbits

Hobbits are known for their love of pipeweed, as well as their creator J.R.R. Tolkien. And did you ever notice that Tolkien’s world is largely a man’s world? Pipe smoking and the war against evil. Must be a man thing.

Huck Finn

Mark Twain loved smoking. For him, the pipe and the cigar were symbols of rebellion against the constraints of an oppressive and unfair society. Huck Finn is an iconoclast; and through him, Twain attacks the social conventions and repression of his day. And Huck Finn smoked a pipe.

My Fictional Pipe Smokers

In my own writing, most of my main characters smoke a pipe. Why? Because a man who smokes a pipe is a thinking man. A man who approaches life calmly and rationally.

A pipe smoker is a meditative man. A man who contemplates and ponders the deep things of life.

Bill Arthur

Bill Arthur is such a man. He is the main character in my post-apocalyptic series The Rocheport Saga.

Bill’s main goal is to use the knowledge we already have to prevent humanity from slipping back into the dark ages. He is an armchair philosopher, who reluctantly becomes a leader.

Early on, Bill smokes Briggs Pipe Mixture: “When a feller needs a friend.” Because being the leader is often a lonely job. A pipe can however bring solace to a troubled soul. A pipe is sometimes a man’s best friend.

Harry Wright

Justinia Wright may smoke cigars at a rate to rival Sir Winston Churchill’s daily consumption, but her brother Harry is an occasional pipe smoker. He may not be the brains behind the detective agency, but he is the one who keeps it running.

Harry Thurgood

Harry Thurgood, the coffee shop owner in Magnolia Bluff, Texas, smokes a pipe. And I believe he’s the only smoker amongst the main characters in the Magnolia Bluff Crime Chronicles series.

He is a man with a secret life that he wants to keep a secret. But he’s also a man who enjoys the finer things in life. And the pipe can make a man look very distinguished.

Dr. Rafe Bardon

Pierce Mostyn doesn’t smoke. But his boss, Dr. Rafe Bardon is a pipe smoker. Bardon is the general behind the lines directing the troops who will save the world from Cthulhu and his ilk.

For Myself

For myself, the creator of fictional heroes and heroines, I enjoy my pipe. Sitting out in the garage, with a mug of tea and my pipe, I contemplate life and spin yarns in my head. Sometimes, though, I just do nothing. After all, when one has the two best leaves on the planet, tea and tobacco, what more does one want? That is pure contentment.

The Brotherhood of the Pipe

The Brotherhood of the Pipe, both in fiction and the real world, is still alive and well.

In my writing, as in Twain’s, pipe smoking is part of my rebellion against those elements of our government and our society that would squash our liberty because they think they know what’s best for us.

Huck Finn thumbed his nose at all the do-gooders who would cheat us and take away our freedom.

Huck smoked corn cob pipe. And I do, too.

Comments are always welcome! And until next time, happy reading!

CW Hawes is a playwright; award-winning poet; and a fictioneer, with a bestselling novel. He’s also an armchair philosopher, political theorist, social commentator, and traveler. He loves a good cup of tea and agrees that everything’s better with pizza.

CW Hawes is a playwright; award-winning poet; and a fictioneer, with a bestselling novel. He’s also an armchair philosopher, political theorist, social commentator, and traveler. He loves a good cup of tea and agrees that everything’s better with pizza.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider buying me a cup of tea. Thanks! PayPal.me/CWHawes

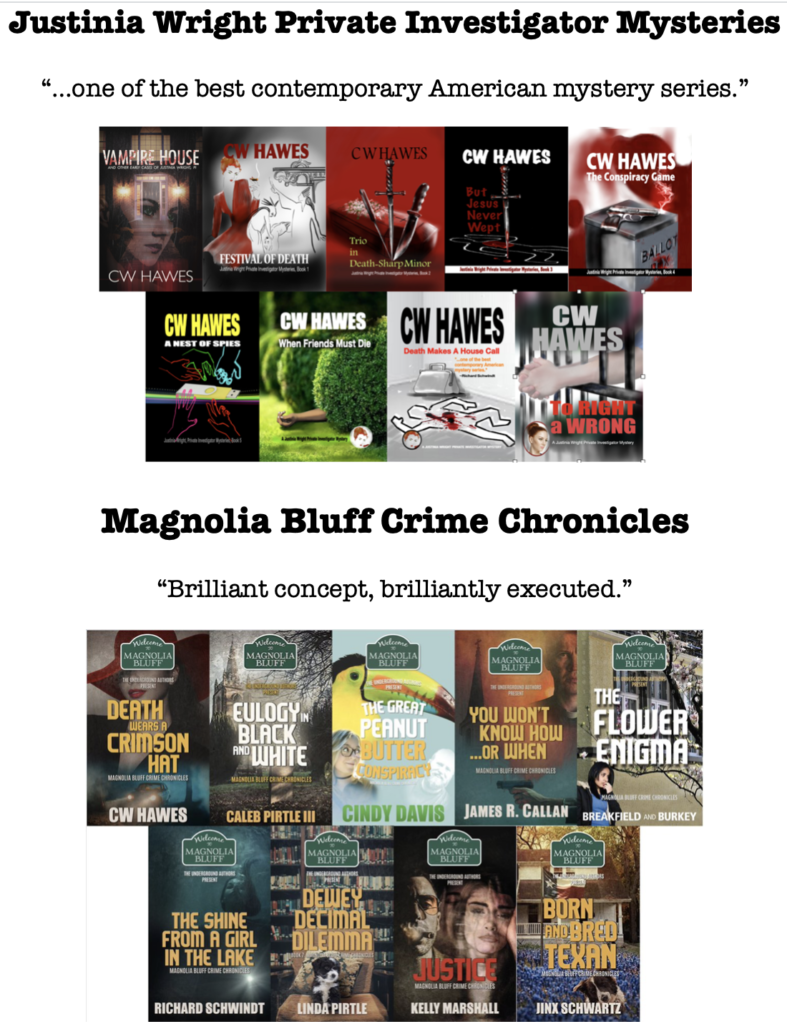

Justinia Wright Private Investigator Mysteries on Amazon!

Magnolia Bluff Crime Chronicles on Amazon!

Share This!